Blog

The Faces of the Meiji Emperor: Development and Genesis of the Imperial Image in the Context of the Visual Culture of the Meiji Period

1 Introduction

The official representation of the Japanese emperor underwent a fundamental realignment during the Meiji period. A central role in this process was played by the goshin-ei, a photorealistic chalk drawing of the emperor that was circulated as his official portrait. While photography as a technological medium was gaining increasing importance, it was the goshin-ei—a chalk drawing of Emperor Meiji—that became the official representation of his person. Practical reasons, such as the problematic relationship of the Meiji emperor to photography, offer one set of explanations for this development. Yet, in the context of the specific visual culture of the Meiji era, additional interpretations emerge that help to explain this exceptional case.

Why was it acceptable, or even advantageous, to depict the emperor in a painterly medium? In Europe, photographs were already being used to produce and distribute portraits of rulers on a mass scale, especially in those monarchies with which Japan sought to catch up in terms of power and prestige. No other Japanese emperor before or after Emperor Meiji was depicted so extensively in the medium of the woodblock print. And while Meiji himself never really warmed to photography during his lifetime, his son, the Taisho emperor, and his consort Empress Teimei were photographed and represented significantly more frequently.

In order to address the questions arising from this observation, I conduct a comparative and chronological analysis of selected woodblock prints of the Meiji emperor. My aim is to make the visual representation of the Meiji emperor comprehensible within the cultural context of the Meiji period. Building on this, and drawing on the theoretical approaches of Kracauer and Barthes regarding the effects of photography, I investigate the extent to which the deliberate turn away from photographic staging of the emperor supported—or possibly even hindered—the ideological objectives of the Meiji state.

2 The Meiji Emperor: Face of the Modern Nation-State

The Meiji Restoration of 1868 marked not only a political upheaval but also a shift toward a deliberate staging of the emperor as a symbol of the nation. The new rulers, a group of young, Western-oriented samurai, placed the previously powerless Meiji emperor at the center of a state-supporting ideology. Although he initially exercised hardly any governmental authority, he was now tasked with embodying culture, tradition, and the historical continuity of Japan. The person of the emperor provided the emerging nation-state with a tangible face that could offer a common patriotic point of reference to a previously federated and fragmented country.

The practice of giving heads of state memorable images and a public presence was, however, not a uniquely Japanese phenomenon in the nineteenth century. In Europe and elsewhere, rulers staged themselves as personified symbols of their nations or empires. The result was a proliferation of portraits, monuments, and public ceremonies with the aim of legitimizing the ruling order by fostering identification between the population and the monarch. Queen Victoria, for example, made extensive use of photography after being proclaimed Empress of India in 1876. Photographs showing her in majestic posture, wearing crown and regalia, served to embody her enhanced power and responsibilities.

Whereas European monarchies could fundamentally draw on a long tradition of public ruler images, the emerging visualization of sovereign authority in Japan represented a break with past practice. Unlike European absolutist rulers, the shogunate—presumably because its legitimacy rested on other foundations—had never sought to glorify its leaders personally in the broad public sphere. Officially, the shoguns ruled “in the name of the emperor,” who resided in Kyoto as the nominal head of state and spiritual authority. When, in the final phase of the shogunate, an awareness of the importance of visual self-representation slowly emerged, and a comprehensive series of woodblock prints depicting the shogun on his travels was commissioned, it was already too late. The shogunate, already weakened, stood on the verge of collapse, and power soon passed to the emperor and the architects of the Restoration.

With the goal of lending visibility to the emperor and gradually aligning the state ideologically around him, the new elites began implementing extensive measures of visual and ceremonial staging. Yet, whereas European monarchies were challenged by parliamentarism and revolutionary currents and therefore used photography to present their rulers in a deliberately “people-oriented” manner, the representation of the Meiji emperor tended to be elevated and solemn. The following section therefore provides an overview of two influential forms of visual representation, woodblock print and photography, and lays the foundation for a more detailed examination of imperial imagery.

3 Images of Progress: Photography and Woodblock Print in an Era of Change

3.1 Japan’s Tentative Beginnings with Photography

The history of photography in Japan begins technically in 1843 with the introduction of the first daguerreotype camera by Dutch traders. Due to unclear circumstances, the camera remained aboard the ship, delaying the start of practical engagement with photography. In 1848, the merchant Ueno Toshinojo finally purchased the first daguerreotype camera in Japan and soon brought it to the court of the Satsuma domain. Initial experiments with the new technology met with only moderate success. However, in 1854, the first successful photographic exposure was achieved, and a small piece of history was written.

The further exploration and testing of photography took place under favorable conditions in Japan. In Satsuma, photography was regarded as an essential component of the broader effort to master Western science and technology. Its spread—initially within Satsuma and later across Japan—can therefore be understood in the context of a general sense of political and social awakening that coincided with growing interest in Western technology. Contrary to the popular belief that a person’s lifespan shortened with every photograph taken, portrait photography rapidly grew in popularity in Japan.

Soon after, the young Meiji state began to use photography in both documentary and ideological ways in the context of the colonization of Hokkaido. Photographs taken there were intended to document and promote the settlement and development of the island, and to depict its transformation from a “wild” landscape into a space of civilizational progress. In this way, Japan discovered the power of images in the early years of Meiji rule, and photography became a central medium of meaning-making in the period.

3.2 The Woodblock Print: From Popular Medium to Art Form

While photography was establishing itself as a new form of visual representation and documentation, traditional woodblock prints retained their significance. In the early 1870s, the publishing sector was still in its infancy, and literacy rates remained relatively low. Woodblock prints, especially the colorful nishiki-e, served as an important source of information for the broader population. Because such prints were comparatively inexpensive to produce, in contrast to photographs, they dominated documentary visual culture in the early and mid-Meiji period.

Even as photography gained ground over time, woodblock prints continued to play an important role in the dissemination of information. Only later did the medium gradually evolve—from its original function—into an autonomous art form. It was also not uncommon for woodblock prints to be used for propagandistic purposes, especially in support of the state’s economic policies. Some prints, for instance, depicted working conditions in silk mills in an idealized manner in order to persuade rural families to send their daughters to work in the cities.

With the enthronement of Emperor Meiji, new motifs emerged that reflected the changing focus of society. The emperor became an increasingly common subject in woodblock prints. As he rose to the position of leading figure in the Meiji state, he began to travel throughout the country and present himself to his subjects. The woodblock print took up his travels as a popular motif and staged the emperor in a way that reflected his new role as a state-bearing monarch.

The mode of representation in the woodblock print was not static but underwent a gradual development into the early twentieth century. This process, and the structural conditions that allowed the idea of the emperorship as a politically legitimate form of rule to unfold in society through the medium of the woodblock print, are the subject of the following chapter.

4 Between Tradition and Political Ambition: The Visual Policy of Emperor Meiji Before 1872

The staging of the emperor in Meiji-period woodblock prints benefited greatly from changing conditions in the printing industry. Production methods were refined, and the possibilities for quantitative reproduction increased markedly. Within roughly thirty years from the beginning of the Meiji period, more prints were sold than in the entire 200 years under Tokugawa rule.

What Benedict Anderson calls “print capitalism,” which he associates with the emergence of modern nation-states, is also evident in Japan in the expansive proliferation of woodblock prints at the start of the Meiji era. The high print runs and widespread distribution of these works fostered a new sense of simultaneity of events across the country. For viewers, woodblock prints could create the feeling of having seen the emperor personally and thereby of having become a witness to the ongoing process of national unification. In their role as an effective means of communication, the prints obscured the fact that individual subjects often lived thousands of kilometers apart and would never actually meet.

In parallel with this remarkable increase in productivity, the depiction of the emperor also underwent a transformation. The following section illustrates this development by examining selected works and highlighting key turning points in representation. These reflections also provide an analytical framework for the later, more detailed discussion of the goshin-ei.

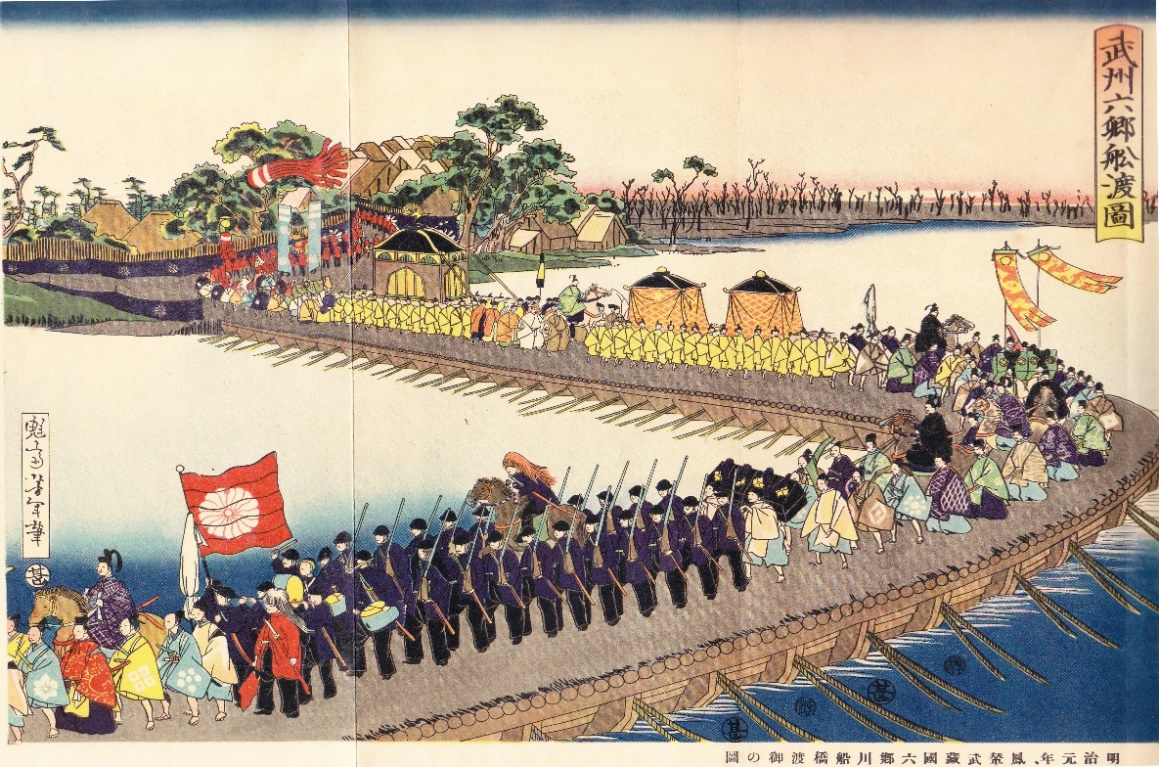

4.1 The Invisible Emperor

The earliest prints that gained popularity from 1869 onwards deliberately employed the non-depiction of the emperor as a means of preserving and affirming his sacral nature. Rather than portraying him directly, they merely suggested his presence. Typically, such prints depicted imperial processions through Japan. The subject of the emperor travelling was not unusual, nor was his non-depiction. Already in the Edo period, processions—due to the system of alternate attendance and sankin-kotai—were a fixed part of everyday life. The non-depiction of central figures was a demanded standard under the shogunate’s censorship laws.

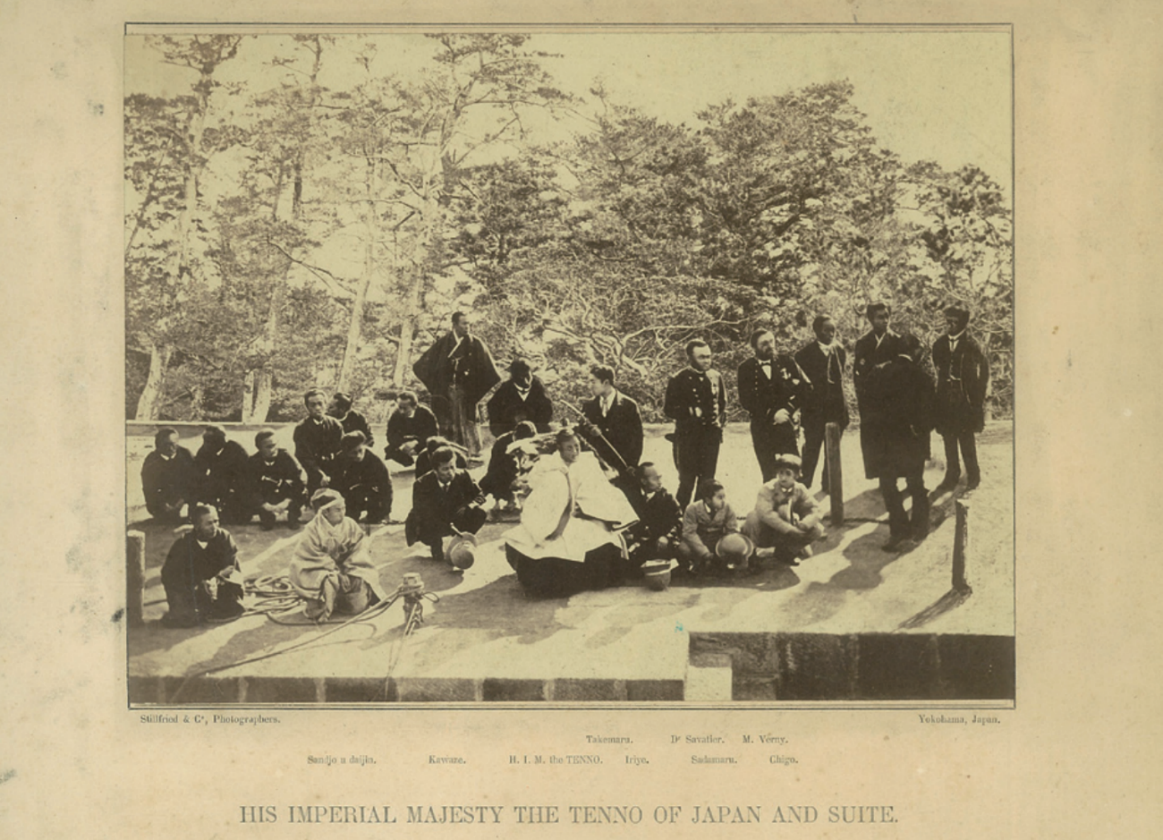

One of the earliest images of Emperor Meiji (Fig. 1) shows him symbolically indicated while crossing the Rokugo River. It is noteworthy that the title of the work meticulously specifies the location but avoids any direct reference to the emperor. This was typical of woodblock prints of the time, which possessed a journalistic character without explicitly declaring it. The focus of the image lies on the political and social impact of the emperor.

Whereas later images depicted the emperor as a physical being and, on that basis, established more complex meaning relations, these early depictions emerged at a time when efforts were still underway to achieve territorial unification of Japan. Tsukioka’s portrayal of the Rokugo crossing can be interpreted in this context. Although the expanse of the river visibly exceeds the picture’s perspective, it does not prevent the emperor and his entourage from crossing. Overcoming water—especially in light of Japan’s geographical characteristics—underscores the cohesive power of the emperor and conveys an impression of imperial reach and control. This non-depiction and thematically limited treatment of the emperor in woodblock prints changed abruptly after 1872, when he was photographed for the first time.

4.2 The Visible Emperor

By 1872 at the latest, Emperor Meiji was travelling the country by carriage and thus became visible to all those present—a step that primarily served to consolidate his public role. In 1871, a public western-style dress code had already been introduced, so that in 1872 the emperor appeared in public for the first time in Western-style attire. This shift was preceded by a serious diplomatic incident that appears to have influenced the way in which the emperor henceforth presented himself in public.

4.2.1 First Unofficial Photograph of the Meiji Emperor

In January 1872, the Meiji state was alarmed by the appearance of unofficial photographs of the emperor, which brought the question of controlling his visual representation to the forefront. The author of these scandalous images was the Austrian photographer Raimund von Stillfried-Rathenitz. While the emperor was inaugurating a Franco-Japanese joint project, Stillfried concealed himself on a ship in the adjoining dock and photographed the scene through a hole in the sail.

When Stillfried attempted to advertise and sell the photographs a week later, negotiations at the highest level quickly ensued. Because Stillfried was resident in Yokohama, he was not directly subject to the Meiji government’s jurisdiction, which complicated the confiscation of the photos. After some diplomatic wrangling, however, the government succeeded in compelling him to surrender the negatives, thereby preventing the unwanted spread of the images.

In retrospect, the incident proved instructive: it made clear that the mass reproducibility of photographic works and the spontaneous, authentic character of the medium presented a potential danger to the desired image of the emperor and, by extension, to the young state itself. Maria Carbune argues that the deeper problem with this photograph lay in the unregulated nature of the encounter between the emperor and the other people depicted. Unlike commercially distributed imperial portraits, the image did not reproduce imperial authority but rather undermined it.

The depiction and dissemination of the emperor in nishiki-e prints had been tolerated precisely because they occurred under the tacit agreement that he would never be named directly as such. The nature of photography did not allow for such a conciliatory approach, since there was no plausible basis for an alternative interpretation of the person shown. What Barthes describes as the “emanation of the referent” is permanently fixed in the image by the technological process of its creation. The light that struck Stillfried’s camera recorded the emperor’s contours and mercilessly exposed the awareness of his real presence in the photograph.

4.2.2 First Official Photographs of the Meiji Emperor

In response to the scandal, the first official portrait photographs of Emperor Meiji were produced in 1872. Gartlan sees the commissioning of these portraits as a direct consequence of Stillfried’s unofficial images, and the tight chronological sequence seems to support this view. Stillfried’s photograph was taken in January 1872; shortly thereafter, Uchida Kuichi was commissioned, and the first portraits were completed in September of the same year.

Uchida initially produced a series of photographs showing the emperor both in traditional court robes and in European-style uniform. Although these images were handed over to the envoys of the Iwakura Mission for official representation abroad, the authorities were not fully satisfied with how the emperor appeared. Government officials in particular objected to the traditional styling and aimed for a representation that would more clearly display Western symbols of power.

Contrary to how the sources are often summarized, it appears that photographs of the emperor in Western uniform were already taken during Uchida’s first session. This suggests that the deeper problem lay in how the emperor’s body—his facial expression and posture—came across in the images. This can be illustrated by comparing two photographs with similar symbolism but different dates of origin. In the later portrait of 1873, the representation of imperial authority is clearly more successful, so much so that no objections were raised against its controlled distribution. The portrait was endowed with a sacred status, and each prefecture received copies that were displayed on special occasions, such as the emperor’s birthday.

5 Staged Efficacy: Emperor Meiji in Woodblock Prints After 1872

5.1 The Profanization of the Image

With the publication of the imperial portraits and the emperor’s more frequent public appearances, the manner in which he was depicted in woodblock prints changed correspondingly. The gradual detachment of the emperor from myth and the profanization of his image can be traced particularly well in early and later works by Toyohara Chikanobu. Together with Toyohara Kunichika, Chikanobu was one of the most important and productive artists of gosho-e, producing numerous scenes of the imperial family into the late 1880s.

A well-known work by Chikanobu from 1878 shows Emperor Meiji surrounded by his imperial lineage and significant Shinto deities. The emperor, identifiable by his uniform, is located in the lower center of the image. At his feet sits the empress in traditional Japanese attire. The three figures above the emperor represent the deities Izanagi (right), Izanami (left), and Kunitokotachi, the founder of the divine lineage. The entire divine genealogy gazes down on the emperor, as if bestowing their blessing upon him before sending him into the world with a worldly mission.

From 1880 onwards, imperial woodblock prints developed further, and the motifs began to support new ideological narratives of the state. A typical form of representation was the depiction of the imperial family in the style of a European model family, reflecting Meiji policy that aimed to adopt social customs from Victorian Britain. The imperial family thus increasingly became a symbol of Japan’s modernization efforts.

An early pictorial testimony to this shift shows the emperor and his consort at a riding event, both in Western clothing. It is striking that not only the emperor but also the empress is depicted in Western style, in contrast to early portrait photographs from 1872, in which she appears exclusively in traditional dress. This seeming discrepancy can be understood as a deliberate staging that positions the empress in a dual role: as guardian of tradition and as representative of modern Japan. She thus embodies the ideals of the Meiji Restoration, especially the principle of wakon yosai (“Japanese spirit and Western techniques”), which emphasizes a synthesis of national identity and foreign progress.

5.2 Stylization of the Imperial Image

In woodblock prints of the 1880s, an increasingly uniform depiction of the emperor can be observed. The images I have selected are details from an imperial triptych whose shared model is Uchida’s 1873 portrait, to which they appear to refer in terms of symbolism and staging. Although the works are dated at least two and four years apart, closer inspection reveals clear differences in how the emperor’s facial features are rendered.

In Chikanobu’s work, the Westernization of facial features is most pronounced. The face appears more angular and less rounded, and the facial hair is fuller. Nose and eyes are drawn in a more “Western” manner, less curved, and the emperor’s chest is adorned with military decorations. As in the photographic original, the emperor holds the hilt of a sword in his left hand while seated in an armchair. However, the woodblock prints go beyond the photographic image by placing the emperor more upright and with a more strictly formal posture.

These adjustments aim to correct the unsuccessful representation of a Western body ideal in the early photographs. Fiction and reality merge into a synthesized imperial body. Artists increasingly integrated this newly shaped body into their works, gradually distancing the imagery from the photographic original. The imperial image was eventually embedded in a variety of ideological narratives, which the following sections explore.

5.3 Connotation in the Woodblock Print

The highly productive culture of woodblock prints centered on the imperial figure in the 1880s offers fertile ground for a deeper analysis of the meanings constructed by these images. Methodologically, I draw on Roland Barthes’ semiotic model. Barthes developed the concept of myth as a system of communication or a message. He understands myth as a second-order semiological system that builds on an already existing chain of signs. What constitutes a sign in the first system becomes a mere signifier in the second. In this sense, Barthes speaks of a meta-level on which the signs of the first level unfold their effects.

The following reflections operate on precisely this second level, where the symbolism of imperial woodblock prints unfolds its overarching significance and produces narratives.

5.3.1 Japan and the West

A common motif in contemporary imperial woodblock prints is the transformation of the Japanese monarchy into a new sui generis model that aspires to unite West and East. In Chikanobu’s “View of the Imperial Excursion to the Circus ‘Charini’,” the emperor presents himself as a connoisseur and admirer of European entertainment culture. In another print, he appears in the Rokumeikan, a pavilion designed under the supervision of Josiah Conder in 1880.

Empress Shoken (center of the image) stands out by wearing a European crinoline dress and a flower-adorned hat. However, Japanese and imperial symbolism also appear in the scene: cherry blossoms in full bloom dominate the background, and at the left edge of the image, a sunshade printed with chrysanthemums (the imperial crest) bends into the picture. The emperor is depicted in a stylistically standardized manner, echoing reference works such as the triptych mentioned earlier. As usual, he wears his black uniform, and, as so often, his hat lies somewhere to the side. Even the armchair from the 1873 photograph seems to follow him from image to image.

Overall, this combination of Western and Japanese elements creates the impression of an effortless, “natural” fusion of the two cultures. The emperor and empress, the image suggests, are the driving forces who usher in Japanese modernity while simultaneously safeguarding traditional values.

5.3.2 The Emperor in the State

Toward the late 1880s and early 1890s, the emperor’s representation increasingly emphasizes his role as commander-in-chief of the armed forces. In one print, he is still inspecting the orderly parade of his troops. In another, produced at the beginning of the 1890s in the context of growing geopolitical tensions with China, the visual language becomes markedly more martial. The emperor is no longer merely an allegory of national unification; his significance expands beyond that of a moral and ethical exemplar (as in earlier family scenes) to encompass a real political claim to leadership in both civil and military matters.

Although these images clearly express notions of military dominance and national pride, they also normalize the emperor’s assigned role within the state and armed forces. As photography grew more popular, woodblock prints also sought to depict apparent reality in ever greater detail. Finally, in 1888, a chalk drawing emerged that, although not a woodblock print, claimed for itself the authenticity of a photographic vision and brought the imperial image to a final, canonical form.

6 The Goshin-ei

The goshin-ei marked the culmination of a series of works initiated by the Imperial Household Ministry. In 1874, Goseda Horyu produced a portrait of the emperor in a Western-inspired manner, commissioned by the court. During the process, Goseda relied on photographs by Uchida Kuichi to capture Emperor Meiji’s characteristic facial features. With mineral pigments on silk, he created an image that gives the viewer an almost tangible sense of three-dimensionality.

Shortly thereafter, the court commissioned two further oil portraits from Giuseppe Ugolini and Takahashi Yuichi, both trained in Western oil painting. Takahashi, in particular, emphasized the advantages of depicting the emperor in oil, since the medium, like photography, promised a high degree of visual accuracy. Both works show the emperor in a European military uniform similar to those seen in woodblock prints of the 1870s. The artists each made slight modifications to his posture—Takahashi, for example, enlarged the emperor’s head disproportionately.

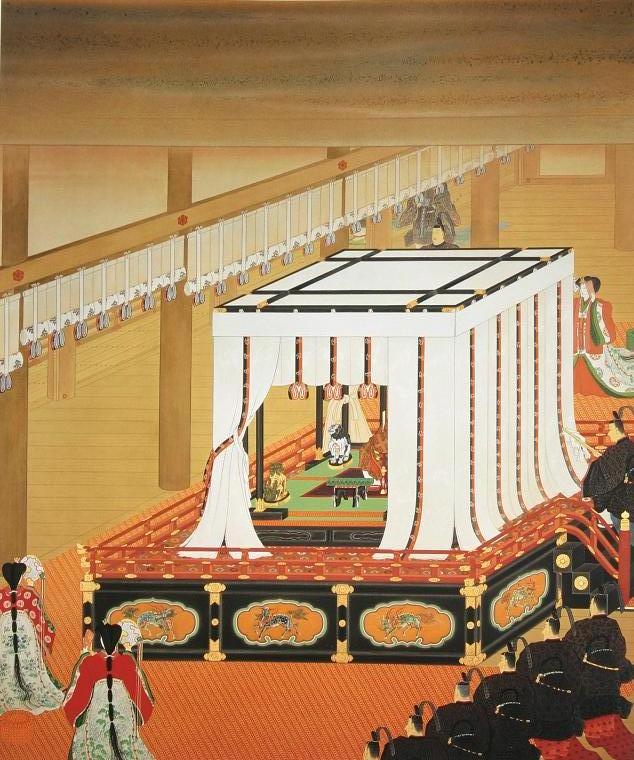

6.1 Background to the Creation of the Goshin-ei

With the creation of the goshin-ei—literally “august shadow”—in 1888, the official depiction of the emperor was finally consolidated, and even the term itself represented something new. Previously, the Meiji government had referred to circulating portraits of the emperor as go-shashin (“august photographs”), a category that encompassed all realistic imperial depictions. By around 1888, however, many of these images had become inaccurate with respect to the emperor’s appearance. Fifteen years had passed since the earlier portraits, and the emperor had visibly aged.

Consequently, there was a clear desire to produce new portrait photographs. This wish could not be realized, however, because the emperor steadfastly refused to be photographed again. The court therefore turned to the Italian artist Edoardo Chiossone, who had already made a name for himself in Japan with his naturalistic drawings, often based on photographs. Because the emperor again declined to sit for a photograph, Chiossone had to rely on his powers of observation. He studied the emperor’s features from a distance and, without Meiji’s knowledge, incorporated his impressions into a Conte chalk drawing.

By 1888 the drawing was completed. Although it was not an entirely faithful likeness, it was soon reproduced photographically thousands of times and sent to middle and normal schools in the prefectures. The emperor did not explicitly consent to the dissemination of his image, but he tacitly approved it by signing some of the photographs.

6.1.1 The Appearance of a Photograph

At first glance, the goshin-ei gives the impression of being an authentic photograph of Emperor Meiji, and its photographic reproduction reinforced this claim to authenticity. Even the term goshin-ei supports this interpretation by invoking proximity to photography. As “august shadow,” the name can be read—whether intentionally or not—as echoing reflections on the nature of photography. The shadow metaphor alludes to the indexical dimension of photography that the image seeks to appropriate. Just as photographs preserve an imprint of a person’s real existence, the goshin-ei, referring to itself as a “shadow,” evokes a trace of the emperor.

6.1.2 Visual Elements in the Goshin-ei

Yet the emperor as drawn by Chiossone is far from an authentic representation. On the contrary, the image shows not the emanation of the referent but a clearly idealized, Westernized emperor whose gaze and posture convey determination. He appears more mature, projects greater virility, and his upper body seems unusually muscular for an average Japanese man of the time. Wakakuwa Midori notes that the pose—in which the emperor holds a sword in one hand while the other, clenched in a fist, rests on a table—strongly resembles portraits of contemporary Italian kings. The exaggerated musculature might moreover reflect Chiossone’s reliance on his own self-portraits as a reference, resulting in a more European body type.

In other respects, too, the goshin-ei is unusual among portraits of kings and emperors. Executed by the hand and mind of an artist, it appears relatively plain compared to works that highlight the exalted status of their monarchic subjects by making full use of the possibilities of painting. As late as 1890, the newly crowned Kaiser Wilhelm II had himself portrayed in a highly dramatic oil painting by Max Koner. The Meiji government, however, deliberately chose a more restrained depiction, positioning the goshin-ei somewhere between photograph and painting. As a photograph, it would have appeared too contrast-heavy, linear, and lacking in shading to be fully convincing; as a painting, it was unusually austere.

At the same time, the goshin-ei demonstrates how important photographic authenticity was for the Meiji state and how closely realism in painting was associated with photography. Historically, however, the work was also exceptional. In Europe, portrait photography in the format of the carte de visite was on the rise, enabling the widespread circulation of images in which monarchs presented themselves as “bourgeois” sovereigns. In Japan, too, there was already great interest in photographs of courtesans, actors, and other celebrities, whose images were sold as carte de visite from the mid-1870s onward.

In principle, the goshin-ei could have been disseminated under similar conditions. Yet such treatment would have required a profanization of the emperor’s person that the state wished to avoid. The goshin-ei was more than a decorative souvenir; it was the definitive image of Emperor Meiji that remained binding until his death and beyond.

6.2 Function of the Image and Ideological Instrumentalization

By fixing the emperor’s appearance in a final image, the Meiji state aimed primarily to regain interpretive control over his visual representation. This control had partly slipped away because numerous prints—especially lithographs—based on Uchida’s photographs were in circulation, and there was concern that they were drifting too far from their photographic prototype. There was also the fear that the emperor’s image might lose its aura through overexposure. The deliberate scarcity of the goshin-ei and the restricted access to it—only at specific locations and on particular occasions—supports this latter view.

The way the goshin-ei was handled also underscores its function as a cult object in a new social order, in which the emperor’s religious and political role was being elevated. Shimazono describes the period between 1890 and 1910 as the “establishment phase” of State Shinto. Exemplary of this era is the Imperial Rescript on Education, which propagated the idea of kokutai: the notion that Japan’s national identity is inseparably tied to the divine lineage of the emperor, and that unconditional loyalty and moral unity form the foundation of the state order.

School curricula of the 1890s likewise reflect the growing sacralization of the monarchy. Textbooks began to integrate the emperor’s descent from the sun goddess Amaterasu as factual national history, rather than merely mentioning it in discursive contexts related to kokutai. Against this backdrop, it becomes understandable that the goshin-ei would be received and used as a cult object. The question remains, however, to what extent the goshin-ei was suitable as an image medium to demand such cult status—an issue I now examine using theoretical approaches to photography.

6.2.1 Temporality in the Image: Death and Transience in Photography

Given that the 1890s were marked by a stronger ideological fixation of the emperor within the state, emphasizing his divine roots, the peculiar case of the goshin-ei may be better understood from a phototheoretical perspective. In his 1927 essay “Photography,” Siegfried Kracauer makes several noteworthy observations. According to Kracauer, photography involves three intertwined temporal dimensions: the temporality within the image, the temporality of the image, and the moment of viewing in the here and now. The interaction of these axes leads, in his view, to a necessary estrangement effect: the old photograph, as a fragment of the past, fails to connect meaningfully with the present.

Kracauer goes further, suggesting that looking at old photographs induces a chill in the viewer. In his words:

“What emerges in the photograph is not the man himself, but the sum of what can be subtracted from him. It destroys him by depicting him, and if he were to coincide with it, he would no longer exist.”

What can be subtracted from the photographed subject and still remain, Kracauer argues, is merely the spatial configuration of a moment; everything else is filtered out. These considerations are highly relevant to the use of the goshin-ei as a cult object in schools and government institutions. If we adopt Kracauer’s understanding, legitimate doubts arise as to whether a photographic portrait of the emperor could have fulfilled its cultic function to the same extent.

Barthes also reflects on the temporality of photography but uses even more drastic terms. For him, photography does not preserve the depicted subject for eternity; instead, it reveals the subject’s death. The photographed emperor, in this view, would be annihilated by the act of depiction. This perception affects both the viewer and the person portrayed and may even help to explain the emperor’s aversion to photography.

Had the final image of the emperor been a mere photograph, I argue, it would have been less suitable as a cult object in light of these “side effects.” The goshin-ei’s ambiguity removes it from a purely photographic reading and strengthens the emperor’s ideological figure. Unlike a photograph, the goshin-ei does not hermeneutically encapsulate the emperor’s essence; rather, it renders him more elusive and lends the image a transcendent character. As a quasi-photographic image medium, it simultaneously fulfilled the demand for visual accuracy and enabled its use as a cult object.

6.2.2 Harmonization

Furthermore, I see the goshin-ei as the continuation of a representational tradition that had developed in contemporary woodblock prints over the years. Just as the emperor was already heavily symbolized in those prints, this symbolism is also present in the goshin-ei. In woodblock prints, the emperor had long been depicted as more masculine, more European, and more expressive than in his earliest photographs. (cf. Figs. 8, 9, 10 in the original work)

Photography first showed a “backward” emperor (as in Stillfried’s image), then a boyish figure visibly uncomfortable as a photographic subject, and finally a man who seemed to have turned his back on photography altogether. In woodblock prints, by contrast, the emperor appeared in all his state-bearing roles: as military leader, loving father, and European-style monarch. In this way, the woodblock print contributed significantly to the discursive construction of the emperorship.

The goshin-ei fitted seamlessly into this visual world without altering the underlying message. I argue that this was possible because the representational forms in the woodblock print and in the goshin-ei were symbolically in harmony, and because both were realistic enough to satisfy the demand for authenticity, yet imprecise enough to preserve an aura of extraordinariness. In Barthes’ terms, they were similar in their function as signifiers—more similar, in fact, than any straightforward photograph of Meiji could have been.

7 Conclusion

In this paper, I have attempted to sketch a selective, chronological account of the Meiji emperor’s depiction within the visual culture of the early and late Meiji period. The pictorial representation of the emperor initially aimed to establish the idea of emperorship as an integral part of society. From the 1870s onward, this early form of representation—characterized by the non-depiction of the emperor—gave way to the introduction of his physical body into the visual discourse.

This development was facilitated in particular by the introduction of photography and its gradual establishment from the 1870s. At the same time, a demand emerged for accurate and authentic representation, in response to which photography and realism worked closely together. With the goshin-ei, a new image medium emerged in 1888 that stood firmly in this tradition and blurred the boundaries between painting and photography.

I have further sought to show how the goshin-ei was able to exploit its dual nature in order to fulfill its function as a cult object. As an image medium, it combined the ideal of accuracy with room for a transcendent interpretation of the emperor’s figure. This union of precision and transcendence facilitated its use within a state cult that coalesced around the image from the 1890s onward. The emperor’s birthdays were accompanied by the collective paying of respects by entire school classes before the image, and in some prefectures teachers were instructed to spend the night at school to guard it. The cult was on the verge of engulfing society and would release it only half a century later, and then only through violence.

References

Anderson, Benedict: Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. 3rd ed. London: Verso.

Asia for Educators: The Meiji Restoration and Modernization. URL: https://afe.easia.columbia.edu/special/japan_1750_meiji.htm [accessed 20.03.2025].

Barthes, Roland: Mythologies. New York: Noonday Press, Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Barthes, Roland: Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Translated by Richard Howard. New York: Hill & Wang.

Carbune, Maria: Nation-Building Through Imperial Images: Fragility and Charisma of Emperor Meiji’s Public Persona. In: Annali di Ca’ Foscari. Serie orientale 59 (3), pp. 157–194. DOI: 10.30687/AnnOr/2385-3042/2023/02/006.

Dower, John W.: A Century of Japanese Photography. 1st ed. New York: Pantheon Books.

Fukuoka, Maki: Selling Portrait Photographs: Early Photographic Business in Asakusa, Japan. In: History of Photography 35 (4), pp. 355–373. DOI: 10.1080/03087298.2011.611425.

Gartlan, Luke: A Career of Japan: Baron Raimund von Stillfried and Early Yokohama Photography. 1st ed. Leiden: BRILL.

Geimer, Peter: Theorien der Fotografie zur Einfuhrung. 5th ed. Hamburg: Junius.

Hinkel, Monika: Toyohara Kunichika: Eine Untersuchung seiner Meiji-zeitlichen Farbholzschnitte unter besonderer Betrachtung der Rezeption von bunmei kaika. Bonn: Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universitat.

Hirayama, Mikiko: The Emperor’s New Clothes: Japanese Visuality and Imperial Portrait Photography. In: History of Photography 33 (2), pp. 165–184. DOI: 10.1080/03087290902768099.

Keene, Donald: Portraits of the Emperor Meiji. In: Impressions 21, pp. 16–29.

Kim, Gyewon: Tracing the Emperor: Photography, Famous Places, and the Imperial Progresses in Prewar Japan. In: Representations 120 (1), pp. 115–150. DOI: 10.1525/rep.2012.120.1.115.

Kitagawa, Joseph M.: The Japanese “Kokutai” (National Community): History and Myth. In: History of Religions 13 (3), pp. 209–226. DOI: 10.1086/462702.

Kobayashi, Tadashi; Okubo, Junichi: Ukiyo-e no kansho kiso chishiki [Basic Knowledge for Appreciating Ukiyo-e]. 3rd ed. Tokyo: Shibundo.

Kracauer, Siegfried; Levin, Thomas Y.: Photography. In: Critical Inquiry 19 (3), pp. 421–436.

Low, Morris: Japan on Display: Photography and the Emperor. 1st ed. London: Routledge.

Miller, Alison: Imperial Images: The Japanese Empress Teimei in Early Twentieth-Century Newspaper Photography. In: Trans Asia Photography 7 (1). DOI: 10.1215/215820251_7-1-103.

Morishima, Yuki: Political and Ritual Usages of Portraits of Japanese Emperors in Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh.

Roth, Carsten: Namensgeschichte. URL: https://www.uni-muenster.de/ZurSacheWWU/quellen/materialien1895.html [accessed 05.03.2025].

Shimazono, Susumu; Murphy, Regan E.: State Shinto in the Lives of the People: The Establishment of Emperor Worship, Modern Nationalism, and Shrine Shinto in Late Meiji. In: Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 36 (1), pp. 93–124. DOI: 10.18874/jjrs.36.1.2009.93-124.

The J. Paul Getty Museum: A Royal Passion: Queen Victoria and Photography. URL: https://www.getty.edu/art/exhibitions/victoria/victoria_photography.html [accessed 20.03.2025].

Tseng, Alice Y.: Imperial Portraiture and Popular Print Media in Early Twentieth-Century Japan. In: The Journal of Japanese Studies 46 (2), pp. 305–344. DOI: 10.1353/jjs.2020.0043.

Varshavskaya, Elena: Marching Through the Floating World: Processions in Ukiyo-e Prints. Providence: Rhode Island School of Design.

Wanczura, Dieter: Tokugawa Shoguns – Rulers of Feudal Japan. URL: https://www.artelino.com/articles/tokugawa-shoguns.asp [accessed 20.03.2025].

Watanabe, Toshio: Josiah Conder’s Rokumeikan: Architecture and National Representation in Meiji Japan. In: Art Journal 55 (3), pp. 21–27.

Yoshie, Hirokazu: The Imperial Portrait and Palace Conservatism in Occupied Japan. In: Japan Review 29, pp. 181–202.

Zohar, Ayelet; Miller, Alison J.: The Visual Culture of Meiji Japan: Negotiating the Transition to Modernity. 1st ed. New York: Routledge.